Mitral Regurgitation

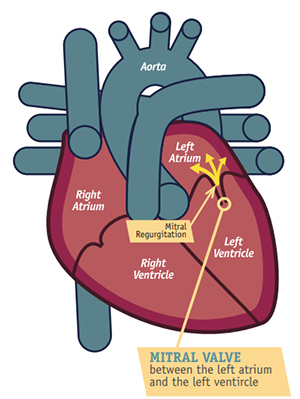

Your blood is supposed to follow a one-way path through your heart. It flows in through the top chamber (the left atrium), down to the bottom chamber (the left ventricle), and then out to your body. Your mitral valve separates these two chambers and keeps the blood from flowing backward.

In mitral valve regurgitation, your mitral valve does not work as it should and allows blood to flow backward into your upper heart chamber.

Mitral valve regurgitation can happen suddenly (acute) or, more commonly, gradually over time (chronic). Acute mitral valve regurgitation is often caused by damage to the heart, perhaps from a heart attack or a heart infection called endocarditis.

There are many possible reasons you can develop chronic mitral valve regurgitation, including mitral valve prolapse, rheumatic heart disease and untreated high blood pressure.

If you have mitral valve regurgitation, you may notice that you feel very tired and that you have a hard time catching your breath when you exercise or when you are lying down. You may also notice swelling in your legs.

Your treatment will depend on the type and severity of your condition and may include medications or surgery. Use this condition center to learn more, create a list of questions to ask your health care provider and get practical tips.

Questions to Ask Your Doctor

If you've been diagnosed with mitral valve regurgitation, there are several key questions that you should ask your cardiologist during your next visit. These questions will ensure that you and your doctor have discussed your major risk factors so that you can become or stay as healthy as possible.

- What is mitral valve regurgitation?

- Why is mitral valve regurgitation important?

- How do I know if I have mitral valve regurgitation? Are there symptoms I should watch for?

- How common is mitral valve regurgitation?

- Is mitral valve regurgitation associated with other diseases?

- Does mitral valve regurgitation require treatment? If so, when?

- What are the treatment options for mitral valve regurgitation?

- Does mitral valve regurgitation make having other valve defects more likely?

- How often should I follow up with my cardiologist or primary care physician for mitral valve regurgitation?

- How is mitral valve regurgitation monitored over time?

- What is the risk of mitral valve regurgitation if it is not corrected?

Overview

The mitral valve separates the left top chamber (atrium) and the left bottom chamber (ventricle) of the heart. It has two very thin flaps called leaflets. Normally, when the leaflets open, blood pumps through. When the leaflets close, they prevent blood from flowing backward.

If your mitral valve does not work correctly, you may have mitral regurgitation, also called mitral valve insufficiency. This means that the valve does not close tightly, and some blood flows backward from the left ventricle to the left atrium. When this happens, your heart must work harder to pump that extra blood.

You may not even notice your heart has a small leak, but it can get worse over time. This is known as chronic mitral regurgitation. Larger leaks can cause the heart to weaken, and people usually begin to notice symptoms such as:

- Being short of breath

- Feeling fatigued or tired when doing their usual activities

- Holding on to fluid in their ankles and feet

The leaking can also occur suddenly (for example after a heart attack). This is called acute mitral regurgitation and is an emergency.

Your health care provider may be able to discover the regurgitation by listening to your chest with a stethoscope and hearing a sound called a murmur, which should prompt further testing.

What Causes Mitral Regurgitation?

There are two types of mitral regurgitation (MR):

- Primary MR (degenerative) is caused by a problem with the mitral valve itself.

- Secondary MR (functional) is caused by a problem with the left bottom chamber, or ventricle, of the heart.

Common causes of mitral regurgitation include:

Mitral valve prolapse: The valve's tissue flaps or the tendon cords that anchor the valves are weakened and stretch. The flaps then bulge into the top chamber, or atrium, with each heartbeat.

Rheumatic fever: This can be a complication of untreated strep throat. It can damage the valve in childhood and lead to MR in adults.

Heart attack: A heart attack can cause decreased blood flow to the area of the heart that supports the mitral valve. In turn, the function of the valve is weakened. The change can be quite severe and sudden if the tendon cords are ruptured as a result of the heart attack.

Weakened heart (or cardiomyopathy): Sometimes, the bottom chamber (ventricle) of the heart stretches. When this happens, the mitral valve also is stretched and becomes leaky.

Endocarditis: This bacterial infection can attach to the heart valves and damage the valve tissues.

Trauma: For example, trauma to the chest in a car accident.

Congenital heart defects: Some people are born with either leaky heart valves or enlarged hearts that make it hard for the valves to close.

Drugs: The medications ergotamine and bromocriptine have been linked with mitral regurgitation. Weight loss medication, such as fenfluramine (fen-phen), has also been associated with this valve problem. This medication has been taken off the market. If you have taken these medications in the past, talk to your provider about getting your heart valves checked. Radiation exposure during cancer treatment also could contribute to the valve changing shape.

Age: Over time, your body can deposit calcium around the valves and make it hard for your valves to close tightly.

Signs and Symptoms

People often can have mild or moderate mitral regurgitation without any signs or symptoms. As the condition worsens, people can develop:

- Heart murmur

- Shortness of breath—especially when lying down

- Fatigue

- Swollen feet or ankles

- Heart palpitations

- Chest pain

Please call your provider if you have any of these symptoms.

Teamwork among patients, providers, valve teams, and nurses can help manage your valve condition.

Exams and Tests

During a routine physical exam, your health care provider will listen to your heart with a stethoscope. If your provider hears a heart murmur, he or she may suspect you have mitral regurgitation. The turbulence of blood flow through the valve will prompt the provider to order some tests. Those tests can include the following:

- An ultrasound, or echocardiogram, of your heart helps assess the severity of how leaky the valve is. It also helps categorize your condition as primary or secondary MR.

- A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) is a special type of ultrasound that looks at the mitral valve from a different angle. In this test, a camera is passed down the esophagus through the throat (using moderate sedation) to get a closer look at your heart valves.

- Stress tests may also be ordered to help evaluate any symptoms you might have during exercise.

- A cardiac MRI is a specialized test that looks at the mitral valve in another way to help measure the severity of mitral regurgitation. It can be used if the echocardiogram or stress tests don't provide enough information.

- A coronary angiogram may be performed if the results of other less invasive tests are not consistent with symptoms. A small plastic tube is inserted into an artery in your wrist or groin and pushed all the way up toward the heart. The test can measure the pressures around the valves. Sometimes, the test involves using dye to show where the blood flows once it gets to the heart. This test also can reveal blockages in your heart arteries that could contribute to your symptoms.

Treatment

There are several treatment options for MR depending on the type and severity of regurgitation.

Your health care provider will follow your condition with routine echocardiograms (ultrasounds of the heart) to see how badly the valve is leaking and whether it is worsening over time. According to the ultrasound, your MR may be mild, moderate, or severe.

Your doctor will likely order tests to monitor your condition and decide if you need or are ready to have your valve repaired or replaced. You will work together with your care team to decide which option is best and safest for you. If your MR is considered severe, your provider may refer you to see a heart surgeon, an interventional cardiologist, and other specialists on a valve team.

Treatment options for MR include medical therapy, and repair or replacement.

Living With Mitral Regurgitation

While discussing treatment options with your provider, it is important for you to monitor yourself for the signs and symptoms of worsening mitral regurgitation.

The goal is to keep you out of the hospital by preventing fluid from building up in your lungs. Fluid buildup will make you feel tired, sluggish, and short of breath. You may even have a hard time breathing at night. Some people must sleep upright or propped up with pillows if they retain too much fluid in their lungs.

All together, these symptoms are called congestive heart failure (CHF). If you notice any of them, call your provider at once.

If you find that you suddenly cannot breathe at all, then call 911 for help.

Source: https://www.cardiosmart.org/topics/mitral-regurgitation

Comments